Saed arrives as we finish breakfast. He takes us to our last stop in Nablus- the cemetery. The first grave he shows us is the Shu'bi family's, whom I spoke about yesterday. Again we hear how they met their terrible end. The anger in Saed's voice is unmistakable, as he calls the Israeli soldiers cowards. I agree with his description- if they had any courage, they would have walked into the old city of Nablus, not bulldozed their way from one house to the next.

Saed arrives as we finish breakfast. He takes us to our last stop in Nablus- the cemetery. The first grave he shows us is the Shu'bi family's, whom I spoke about yesterday. Again we hear how they met their terrible end. The anger in Saed's voice is unmistakable, as he calls the Israeli soldiers cowards. I agree with his description- if they had any courage, they would have walked into the old city of Nablus, not bulldozed their way from one house to the next.Walking through the graveyard is a gutwrenching experience. Two teenage brothers killed within months of each other. A mother and son buried next to each other. Row after row of children's graves, some of them infants. A deaf and mute man walking in the street, shot in the back by the Israelis. In all, Nablus has lost approximately 1000 people since the year 2000.

We finish at the grave of Saed's mother, Shaden abu-Hijleh. As he reads out the inscription bearing her name and date of martyrdom, his voice cracks. He manages to say to us, 'We Palestinians are not terrorists. We are peace-loving people. Our violence is born of desperation- the result of 60 years of Israeli oppression. And we feel that the world has abandoned us'.

I have managed to retain my composure throughout this trip. However as we take Saed's leave, this is no longer possible. After a tearful embrace, we part, promising to stay in touch. The others are overwhelmed by emotion as well.

Back at the hotel, we order a servees to take us to Tulkarem, our final stop in the West Bank. An Israeli soldier stops us at a checkpoint. After inspecting our passports, he asks me what the purpose of our visit is. 'We're a multifaith group visiting religious sites', I reply. 'Ok, have a nice day,' he says. I simply turn my face away. Has he ever wished a Palestinian a nice day?

In Tulkarem, we are received by Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, a Palestinian working for the Israeli human rights group B'Tselem. He takes us to meet the governor of Tulkarem, who again voices his helplessness and frustration at the continued harassment of his people by the Wall, the numerous checkpoints around the city, and the omnipresent soldiers. He reminds us that recently, the Israelis released 250 Palestinian prisoners- this was hailed in the world media as a great concession. However what escaped everyone's attention was that more than 300 others were arrested during the same period.

We then proceed to our lodgings for the night. One of our Palestinian friends in Manchester is from Tulkarem, and we are staying with his parents. Once again, we experience the Palestinian hospitality we have come to love- figs, fruit and mint tea. After a brief rest, it is time to hit the road again. Sa'adi takes us to Nazlat 'Isa, a nearby village. Driving through a residential neighbourhood, we notice that the street seems to come to an abrupt end in the distance. As we get a bit nearer, we see why. The hideous Wall goes across it, dividing the village into two.

And in Nazlat 'Isa, it has actually divided a house. I am not joking- the Wall goes through a house, dividing it into two. This has to be one of the most obscene things I have ever seen. The owner is a man called Abdul Haleem Ibrahim al-Hassan. His misery does not end here. The top two storeys have been occupied by the Israeli army, who have placed a rocket launcher on top. The soldiers enter and leave the house with impunity, using his doors and hallways. He had a freshwater well in his garden, which they have destroyed by pouring cement into it. The soldiers also use his electricity and water, for which he receives no payment. It is heartbreaking to hear him say, 'I don't mind them using my roof- but why don't they leave my house alone?' (The pictures of the house are taken from opposite sides of the Wall.)

Abdul's daughter and sister live next to him. But they might as well be in another country, as they are divided from him by the Wall. His land is also on the other side. To visit his family- and farm his land- he has to use an 'agricultural gate' in the Wall which is only open briefly on Thursdays. This gate is 30 km away. This man's story is well known; indeed, he tells us that the British ambassador was here recently. Pictures of his house have been splashed across various international magazines. Yet this outrageous situation continues.

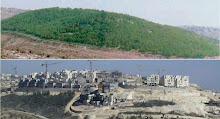

We take his leave, filled with disbelief at what we have seen. We pass the market- or what used to be the market- of Nazlat 'Isa. In January 2003, 82 shops were razed to the ground by Israeli bulldozers in the space of a few hours. In August later that year, the remaining 100 shops were destroyed as well. When the villagers went to court, they were simply told that it was a 'mistake'. Needless to say, the Israelis did not rebuild the shops. The only thing that has been built here is the Wall. 203 Palestinians have land on the other side. They can only access it once a week, and are not allowed to use vehicles to bring their produce back. They must carry it in bags and buckets through a checkpoint. As you can imagine, most of the produce remains unharvested- that which is harvested remains unsold.

Sa'adi takes us to his house for the obligatory mineral water and mint tea. We talk for hours, then drive back to our hosts. While the others rest, I nip out with the father to a Palestinian takeaway- to get some freshly prepared hummus and falafel, fried in front of our eyes. When we return, the mother has laid out some salads and cold meats as well. A simple but absolutely mouthwatering feast.

Sa'adi takes us to his house for the obligatory mineral water and mint tea. We talk for hours, then drive back to our hosts. While the others rest, I nip out with the father to a Palestinian takeaway- to get some freshly prepared hummus and falafel, fried in front of our eyes. When we return, the mother has laid out some salads and cold meats as well. A simple but absolutely mouthwatering feast.After dinner we sit on the patio and drink more mint tea. The local International Solidarity Movement (ISM) coordinator pops in- he has heard that there are some visitors from Britain. He and our host talk about their experiences in Israeli prisons. You will find it hard to meet any Palestinian male who hasn't been to prison- in fact, it is almost a badge of honour. We listen for hours, fascinated. They show us the objects they made in prison to pass the time. Picture frames made out of the plastic of water bottles. An engraving of al-Aqsa on a stone.

The greatest treasure of all is a letter written by the husband to his wife. But this is no ordinary letter. The Israelis only allowed prisoners to write very brief letters, which would be inspected before being posted. The way people got round this was by writing in very small print on cigarette paper, which they would roll up and insert into a medicine capsule. Every time an inmate was released, he would swallow his fellow prisoners' capsules before leaving. You can imagine how the letters were retrieved! They were then given to the respective families.

If there is one thing I have enjoyed the most on this trip, it is talking to ordinary Palestinians. Everyone has a wealth of experience to share. And the hospitality extended by people we have never met before has been overwhelming. The thought that this is our last night in the West Bank is almost too much to bear. However, Jerusalem beckons tomorrow and we need to make an early start.

Tisbah ala-Khair. (Good night)

No comments:

Post a Comment